Entrepreneurship in Colombia Part 1 of 2: History and Institutions

by Lateef Mauricio Abro, at George Mason University School of Policy, Government and International Affairs, March 2012

[Download in PDF Format]

According to the Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index (GEDI), Colombia is currently in the second of five clusters, the “Efficiency transformers” cluster, which indicates that the nation is three clusters away from reaching the paramount goal of entrepreneurship progress, to join the minority in the final “innovation leaders” cluster.[1] This makes sense because Colombia seems to have “done its time” in the factor-driven stage of development having started quite early on in the nation’s history once independence was declared from the Spanish throne in the early 19th century.

Colombia’s Factor-driven Beginnings

By 1853 Colombia’s Commercial Code included two main types of business people, merchants and traders; furthermore, a third designation that was common knowledge, though not found in the Commercial Code of the time, was that of the entrepreneur.[2] In a thorough report about the state of merchants and entrepreneurs in Bucaramanga, Colombia, Maria Fernanda Duque Castro wrote that the terms of “merchant” and “entrepreneurs” aren’t merely economic/legal abstractions, rather, they suggest a larger social reality that links those actors to the state, and local communities and families; furthermore, these designations are just as much economic as they are non-economic. The early businessmen of Colombia created organizations that “provide[d] a structure to human interaction,” paving the way for more mature institutions that would serve to drive economic development and society at large. The early Commercial Code was in fact a formal institution that provided the businessmen, or as North refers to them “players,” with “rules […] to define the way the game is played.”[3] These early foundations of entrepreneurship in Colombia were marked by business that relied on the exploitation of natural resources like gold and copper, and agricultural crops like coffee and tobacco – the industrial sector benefiting from the investment into the development of infrastructure (i.e. roads and railways) that were necessary to support mining and farming activities.[4]

Tail end of Factor-driven stage

Fast forwarding to the early 20th century, in his book “Business History in Latin America,” Carlos Davila calls on a doctoral thesis by Roger Brew to state that industrialization, along with entrepreneurship, wasn’t led by the coffee industry – instead the coffee industry “accelerated processes which had already been generated in the mining industry […] [thus providing] the stimulus for a local and autonomous industrialization in Medellin [,Colombia].”[5]

Thus, we are provided with a decent literature-based background to support the GEDI in suggesting that Colombia is a nation that is making a progressive move towards development, and currently sits somewhere in the efficiency-driven development stage. Colombia’s score in the GEDI’s sub-index for entrepreneurial attitudes has it below only three countries, barely tied with Argentina, and well behind Uruguay and Chile. Colombia’s history has proven that its citizens have a firm enough grasp of entrepreneurial attitudes to facilitate transition into the next GEDI sub-index, “activity,” though it still needs to invest effort into improving the GEDI pillars that fall under that sub-index in which it lags the most: nonfear of failure and cultural support.

Analyzing “Nonfear of Failure”

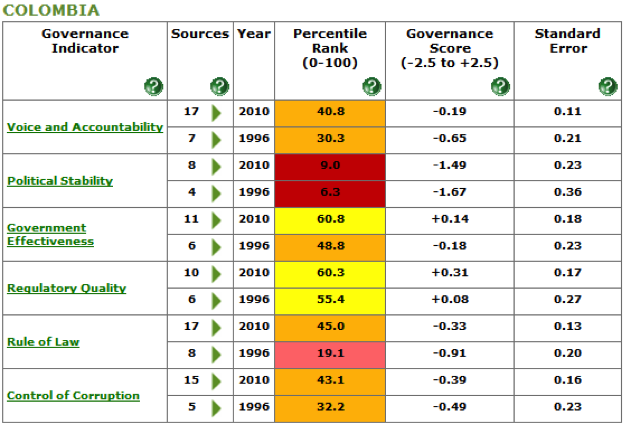

With one of Latin America’s highest unemployment rates (11.2% estimated for 2011)[6], continuing (though slowly waning) hyper-violent internal armed conflict, and over 3.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) placing further burden on the troubled economy, it makes sense that people are hesitant to take the leap into entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is relatively riskier than standard employment, and in some cases it’s simply irrational, particularly in areas affected by outward movement of IDPs and inward movement of non-governmental armed forces. However, drastic improvements in rule of law and government effectiveness, and regulatory quality over the past decade should be allaying concerns of failure – this is perhaps an area where federal institutional support could make relatively low resistance gains in trust since official World Bank numbers (see Figure 1) show improvements in the aforementioned governance indicators.

Analyzing “Cultural Support”

The same positive outlook cannot be conveyed onto the underperforming cultural support pillar because the associated institutional variable, corruption index, because the level of corruption control in Colombia has hardly improved over the past decade. The World Bank’s governance indicators display a percentile rank increase in the “control of corruption” indicator that is far too small, from 32.2 in 1996 to 43.1 in 2010 (see Figure 1). This high level of corruption cancels out the value of ethical steps taken by would-be entrepreneurs as their society’s institutions and organizations are held back from development by the hardened chains of intertwined corruption; furthermore, an entrepreneur that could cope with the institutional and organizational corruption would still have to be able to fleece the pockets of the illegitimate rentseekers that were even more commonplace during the early phases of the factor-driven stage of development. These burdens will hold back the potential of the entrepreneurial concern from becoming a high impact business, thus putting a glass ceiling on the nation’s economic development. A 2006 study conducted by the Corporacion Transparencia por Colombia (Transparency for Colombia Corporation, part of Transparency International) discovered that 84.4% of businessmen stated that they abstained from contracting with the government because competition is unjust, the process is politicized, and kickbacks are commonplace.

| FIGURE 1 |

Worldwide Governance Indicators, World Bank, Accessed 3/9/2012[7] |

Colombia, The Efficiency Transformer

The policy suggestions proposed in the GEDI tell us that Colombia may have adequate enough attitudinal progress to continue improving the “attitude” sub-index while placing key focus on the “actions” sub-index, and beginning to develop the Aspirations sub-index.[8] Institutional support should be deployed to address the two lagging “attitude” sub-index issues of nonfear of failure and corruption to facilitate a continuously positive trajectory for Colombia’s development, otherwise the nation may never actually dominate the “activity” sub-index and if it does its success would be teetering on an unstable foundation that can set the nation back even more than it is now. Colombia has already been down that road of despair, thanks to incredibly violent and consistent armed conflict that dates back to the early 20th century and continues even today. Colombia went through great pains in the 1980s to “fix” its economy by blindly accepting all Washington Consensus principles of economic development and bringing on unilateral trade liberalization. Amidst the tumultuous environment of the times, which are credited not just to bad economics but also to extremely high levels of armed conflict and the world’s largest illicit drug economy, the Washington Consensus wasn’t enough to remedy the situation. This half century of continuous unrest has morphed Colombian society to be one of caution, uncertainty, distrust in the government, and in summary, general complacency; as a result, it is important right now, at a time when armed conflict and drug trafficking is on a clear and projected decline, to implement institutional programs that spur entrepreneurial activity.

Trouble in the Efficiency-driven Stage

Colombians have always been confident business people that display decent numbers in the GEDI for the “opportunity perception” and “opportunity startup” pillars, [9] even amidst substandard government and non-governmental institutional support. The weakest GEDI pillars also make sense, as stated above in Tail end of Factor-driven stage, the weak numbers in the “Nonfear of Failure” pillar is one that can probably be easily remedied, while the “Tech Sector” and “Process Innovation” pillars are seemingly more challenging to fix. The extreme underperformance on these two latter pillars are a result of poor government decisions, capital is invested into national technology sectors that can project a positive return on investment (ROI) – even if domestic businessmen were able to provide positive ROI figures to investors, the political risk factor would bring down the positive ROI projection. Furthermore, this political risk is conducive to “destructive entrepreneurship,”[10] which needs to drop for Colombia to make a clean move into the efficiency-driven stage of economic development. The government has taken great strides over the past decade to reduce political risk by crushing the violent mega cartels that thrived in the 80s and 90s, and logging overdue “wins” against armed political groups such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the United Self-defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). Nevertheless, it is becoming more and more clear that the government’s own house has not been receiving the attention needed to move the public sector away from the corruption, inefficiencies, and unnecessary bureaucracies that came to be as a sort of reaction to the high violence, high terror period between the 1940s and 2000s.

Correcting “Technology Sector” Weakness

In a recent paper published in the International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, the author records a study that proves a correlation between national culture and the nation’s innovation capability.[11] By utilizing Geert Hofstede’s dimensions of culture[12], and grouping nations into three groups based on their level of innovative national culture (INC) we find that Colombia is at the bottom, with an index value of 0.87, higher percentages representing lower innovative national culture. An analysis of three of Hofestede’s dimensions of culture reveals an extreme “low” in the “individualism” dimension (0.07), and relatively low numbers in the “power distance index” (0.31) and “uncertainty avoidance index” (0.37).[13] The low individualism numbers indicate that Colombians are largely collectivist, and as such don’t have the freedoms and outward orientations that are possessed by citizen of a high innovation country like the United States. A deeper analysis into Hofstede’s cultural dimensions tells us that institutional support to increase individualism and reduce uncertainty avoidance can lead to an increase in the “technology sector” GEDI pillar because “SMEs [small, independent manufacturing enterprises] in uncertainty-avoiding societies were [already] prone to sharing technological uncertainty with technology partners in their entrepreneurial pursuits,” and “SMEs in countries with collectivist values […] were more likely to form technology alliances involving equity ties.”[14] There may be hope after all for one of the weakest GEDI pillars, “technology sector,” for Colombia, because its society’s collectivistic and uncertainty avoiding nature may already be favoring an environment that is conducive to cooperative technological innovation between entrepreneurial concerns.

Unproductive Entrepreneurship

A key indicator that a nation is moving into the efficiency-driven development stage is a reduction in Self-employment. As of 2011, “the share of self-employed increased from 20 to 30% over the last 20 years.”[15] This high self-employment rate has been increased over the last two decades for several reasons, with one of the primary reasons likely being related to the 3.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) putting a strain on local economies across Colombia – and this number is project to rise in the coming years according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[16] This brings us back to the painful realities in Colombia that causes its citizens and government officials to lose sleep at night, violent internal conflict. The tragedy is that though progress is being made towards the reduction of violent internal conflict, the remnants of over half a century of Colombia’s internationally record-setting internal conflicts are deeply engrained into society. The governmental challenge is made worse because the negative factors are intertwined and dependent on each other, for example: conflict causes high displacement, which results in less self employment in origin communities and high self employment in destination communities; while increases in internally displaced persons result in an expansion of the informal economy in destination communities.[17] The broader entrepreneurship-specific implications of violent conflict are that high homicide rates result in a reduction of male self-employment (no effect on women self-employment) and as witnessed in Uganda, violent conflict reduced non-agricultural enterprise investment.[18] These last implications may not be completely relevant to Colombian entrepreneurship when desired entrepreneurship means the development of high-impact, established firms with employees (i.e. not self-employed, one-man shops); nevertheless, the facts of research are worth noting.

Conclusion

While Colombia is in the efficiency driven stage of development there are less than desirable achievements in their factor-driven GEDI Attitude sub-index, namely, in the “nonfear of failure” and “cultural support” pillars. That said, both of those factors can be remedied by putting in place the same institutional support that can also be utilized to boost index values on the Activity and Aspirations sub-index pillars that are heavily lacking, “technology sector” and “process innovation.” Colombia’s situation is unique because of the sustained internal violent conflict that has plagued the nation for well over half a century. This internal conflict has become part of society’s psyche and permeated social norms to a point that specific and careful attention is required to sociologically improve the condition of the average Colombian. Given the natural entrepreneurial tendencies of Colombian businessmen, entrepreneurship-related education should not be met with intense resistance; nevertheless, the condition of the average business person, or potential business person, is where resistance will be met. The realities of life in Colombia are such that institutional coaxing and education are necessary to bring up citizens’ business mentality to a level that appreciates the value of each of the GEDI’s individual variables, at least at the Attitude and Activity sub-index level for now, as the Aspiration sub-index becomes a key focus once the nation reaches the innovation stage of development. This “buy-in” from the citizens will be easier met if critical socioeconomic conditions are addressed that convince citizens that corruption is going down, transparency is going up, and educational investment is going up.

ENDNOTES (BIBLIOGRAPHY)

[1] Acs, Zoltan, and Laszlo Szerb. Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2012. Edward Elgar Pub, 2012, p. 45.

[2] Castro, María Fernanda Duque. “Comerciantes y Empresarios De Bucaramanga (1857-1885): Una Aproximación Desde El Neoinstitucionalismo. (Spanish).” Historia Critica, no. 29 (January 2005): 149.

[3] North, Douglass C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 4.

[4] Castro, María Fernanda Duque. “Comerciantes y Empresarios De Bucaramanga (1857-1885): Una Aproximación Desde El Neoinstitucionalismo. (Spanish).” Historia Critica, no. 29 (January 2005): 150.

[5] Guevara, Carlos Dávila L. de, Rory Miller, and University of Liverpool. Institute of Latin American Studies. Business History in Latin America: The Experience of Seven Countries. Liverpool University Press, 1999, p. 87.

[6] “CIA – The World Factbook”, n.d. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/co.html.

[7] “Governance & Anti-Corruption > WGI 1996-2011 Interactive > All Indicators > Country Selection”, n.d. http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/sc_country.asp.

[8] Acs, Zoltan, and Laszlo Szerb. Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2012. Edward Elgar Pub, 2012, p. 36.

[9] Acs, Zoltan, and Laszlo Szerb. Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2012. Edward Elgar Pub, 2012, p. 118.

[10] Ibid, 33.

[11] Sun, Hongyi. “A Meta-analysis on the Influence of National Culture on Innovation Capability.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 10, no. 3/4 (2009): 353.

[12] Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Third Edition. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2010.

[13] Sun, Hongyi. “A Meta-analysis on the Influence of National Culture on Innovation Capability.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 10, no. 3/4 (2009): 358.

[14] Steensma, H. Kevin, Louis Marino, K. Mark Weaver, and Pat H. Dickson. “The Influence of National Culture on the Formation of Technology Alliances by Entrepreneurial Firms.” The Academy of Management Journal 43, no. 5 (October 1, 2000): 966.

[15] Bozzoli, C., T. Brück, and N. Wald. “Self-Employment and Conflict in Colombia” (n.d.), p. 2.

[16] “UNHCR – Colombia”, n.d. http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e492ad6.

[17] Bozzoli, C., T. Brück, and N. Wald. “Self-Employment and Conflict in Colombia” (n.d.), p. 3

[18] Ibid., p. 5